Introduction

The term antimicrobial stewardship (AMS) is defined by NICE as “an organisational or healthcare‑system‑wide approach to promoting and monitoring judicious use of antimicrobials to preserve their future effectiveness”.

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is the loss of antimicrobial effectiveness and, although it evolves naturally, this process is accelerated by the inappropriate or incorrect use of antimicrobials (antibiotics, antifungals, antivirals and antiparasitics).

Very few truly new antibiotics have been developed in the last few decades and we are running out of effective antibiotics for use when they really matter. Direct consequences of infection with resistant micro-organisms can be severe and affect all areas of health, such as prolonged illnesses, longer hospital stays, increased costs and mortality, and reduced protection for patients undergoing operations or procedures. Things taken for granted like hip replacements and neonatal care become much more hazardous.

Pharmacy teams in England have been implementing AMS activities as part of the Pharmacy Quality Scheme in recent years. This includes becoming Antibiotic Guardians, using the TARGET Treating Your Infection leaflets with those who seek advice on self-limiting respiratory tract infections and UTIs, as well as asking patients waiting for an antibiotic prescription to complete the TARGET Antibiotic Checklist.

Natural course of common infections

Prescribing antibiotics in primary care for respiratory tract infections such as sore throat and cough has become commonplace and is often expected by patients, but most of these prescriptions are actually unnecessary.

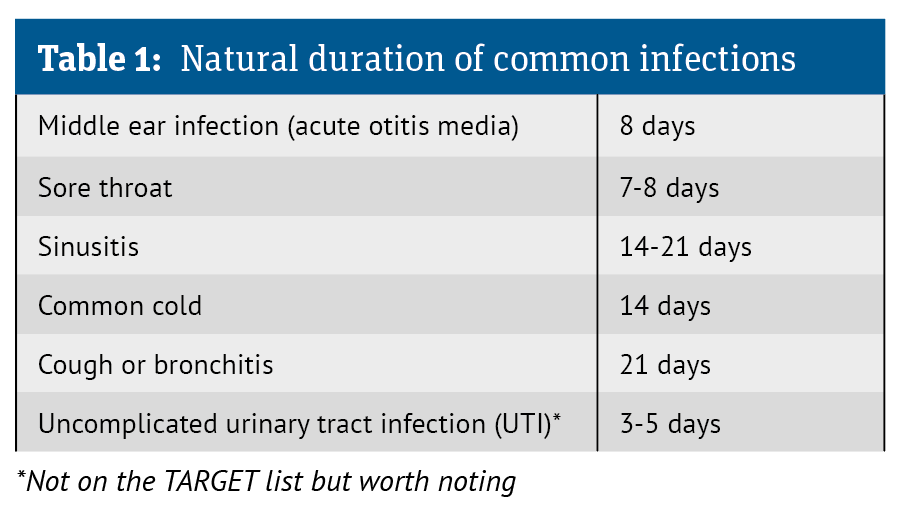

Educating patients about the typical time for common infections to settle is key as many patients and parents believe that infections should clear up more quickly than what the evidence shows is the expected duration.

Misperceptions about the natural course of infections can lead to unwarranted concern that an antibiotic must be needed. The TARGET ‘Most Get Better By...’ list (adapted in Table 1 below) can be used to inform and reassure patients that most infections will resolve in due course without the need for antibiotics.

A barrier to self-care and a driver of primary care consultations is the labelling of OTC medicines where a maximum number of days’ use is specified after which a health professional must be consulted. This may contribute to patient beliefs that the condition should be better by then, and if it is not, then medical intervention must be needed. Pharmacists can reassure patients that by consulting them, the label requirement is met and use of the medicine can continue, if appropriate.