In Clinical

Follow this topic

Bookmark

Record learning outcomes

Obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA) is a common sleep disorder associated with a number of adverse metabolic health consequences. However, many patients with OSA remain undiagnosed simply because a major symptom of the condition is snoring, which is frequently dismissed by bed partners as an annoyance rather than a cause for concern.

Types of sleep apnoea

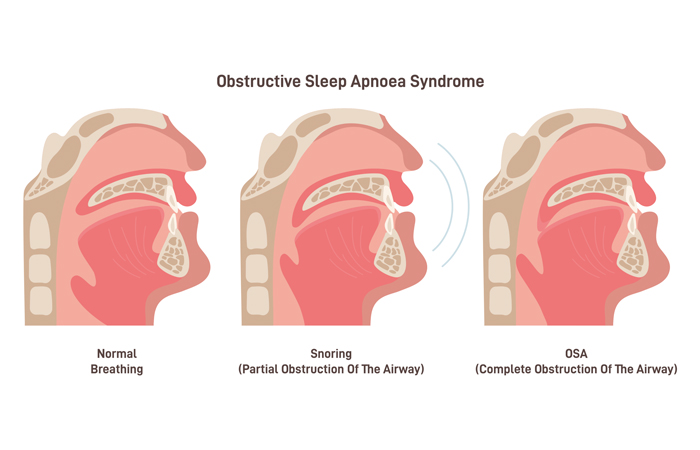

Sleep apnoea is characterised by upper airway obstruction during sleep, leading to transient asphyxia and hypoxia. These repetitive stoppages of the normal breathing cycle during sleep can occur for anywhere between 10 and 30 seconds at a time and arise from either a complete collapse of the upper airways (‘apnoea’) or a narrowing (‘hypopnoea’) of these airways.

There are two main forms of sleep apnoea: central and obstructive. The central type is far less common and develops because the brain is unable to provide effective signals to the breathing muscles. It can be caused by brain-related problems such as a stroke or tumours, other conditions (e.g. heart failure) and even by drugs with a central action, including opioids, gabapentin and valproic acid.

In contrast, obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA) arises because of an increase in the volume of the upper airway tissue, mainly in the lateral pharyngeal, soft palate and tongue areas. This enlargement of tissue volume effectively narrows the airway, making it more prone to collapse and occlusion during sleep. A similar thickening of the pharyngeal walls is seen in those with obesity which, not surprisingly, is an important risk factor for OSA.

OSA: Risk factors and prevalence

Alongside obesity, recognised risk factors for OSA include:

- Increasing age

- Family history

- Being male

- Neck circumference greater than 40.6cm

- Body mass index greater than 30

- Waist circumference above 102cm.

Globally, OSA has been estimated to affect 936 million people between the ages of 30 and 69 years. The prevalence of OSA in the UK is less clear. According to NICE, in 2024, there are an estimated 2.5 million adults affected by the condition. However, writing in a 2020 paper in The Lancet, the authors estimated that around 8 million people in the UK might be affected.

Symptoms

Many people with OSA are probably unaware that they have the condition. Patients are often prompted to seek medical advice due to concerns expressed by bed partners or family members.

Typically, the most common symptom of OSA is snoring, reportedly affecting around 94 per cent of sufferers. However, bed partners might also have been worried by the presence of interrupted snoring, together with sudden awakenings and witnessing their partner gasping for air.

Affected individuals are liable to experience daytime sleepiness and to take regular naps. They also frequently suffer from poor concentration, mood disturbances and fatigue, easily falling asleep while reading or watching television.

Screening

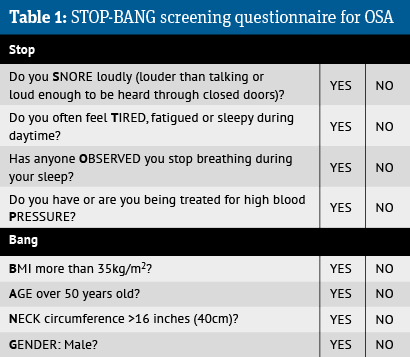

Prior to a formal diagnosis, screening questionnaires can be used to raise the index of suspicion that a patient has OSA. There are several OSA screening tools available, with one such example being STOP-BANG, which is shown in Table 1.

STOP-BANG appears to do a great job at identifying those with OSA, but is much less effective in determining when someone doesn’t have the condition.

The Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) can also be used as part of the patient assessment. The ESS provides a subjective rating of the extent to which patients experience daytime sleepiness, based on the chances of them dosing off in eight commonly encountered scenarios, including sitting and reading or watching television.

Although the ESS is not a useful predictor for OSA, it does serve as a guide to identifying patients who are symptomatic because of their OSA.

Diagnosing OSA

The gold standard diagnostic test for OSA is polysomnography (PSG) or a sleep study test. This is performed while an individual is asleep and undertaken at a specialist sleep centre.

PSG measures parameters including brain waves, blood oxygen levels, heart rate, as well as eye and leg movements. One metric derived from PSG is the apnoea-hypopnoea index (AHI). This has become an internationally recognised tool used to evaluate disease severity in OSA. The index provides a measure of the number of apnoea/hypopnoea episodes per hour and is calculated by dividing the total sleep time by the total number of events.

Using the AHI, there are three different categories of OSA:

- Mild: AHI between five and 14 per hour

- Moderate: AHI between 15 and 30 per hour

- Severe: AHI greater than 30 per hour.

Interestingly, Samsung has included a sleep apnoea detecting feature in its latest smart watch. This feature, which has been approved by the US FDA, uses a built-in sensor that is able to track blood oxygen levels during a user’s sleep. The data is then used to provide an estimate of the AHI.

However, Samsung has made it clear that its smart watch feature is not diagnostic and where there is evidence of OSA, users need to consult a doctor for confirmation of the result.

Scoring

5 to 8 YES responses = High risk of OSA

3 to 4 YES responses = Intermediate risk of OSA

0 to 2 YES responses = Low risk of OSA

How pharmacists might identify patients with OSA

Research suggests that insomnia and OSA frequently co-exist, with between 39 and 58 per cent of patients with OSA also reporting having insomnia. So some patients asking for advice about insomnia may have undetected OSA. Another group worth targeting are patients seeking anti-snoring devices.

Questions to ask are:

- Do you snore? The absence of snoring greatly reduces the possibility that someone has OSA

- Do you get out of breath while you sleep? Repeated and witnessed apnoeas are characteristic of OSA

- Do you fall asleep in situations where you shouldn’t do so?

Even daytime excessive sleepiness should warrant a referral.

Alternatively, pharmacists might want to consider using STOP-BANG with patients who are obese or suffering from hypertension.

There is no doubt that the prevalence of OSA has increased over the past 15 years as levels of obesity have risen, yet many patients with the condition remain undiagnosed.

Ideally placed

Although community pharmacists are ideally placed to help identify undiagnosed OSA in their patients, there is currently no such screening service available in the UK. In contrast, countries like Australia appear to be much further advanced.

In fact, many Australian pharmacies already offer sleep apnoea services and have done so for many years, and the Pharmaceutical Society of Australia has produced guidelines for the provision of pharmacy-based sleep apnoea services.

Here in the UK, a national pharmacy-based OSA screening service could help to reduce the economic burden of OSA on the NHS and increase public awareness of the condition. Additionally, pharmacists could ensure that suspected patients are promptly referred and commenced on CPAP (continuous positive airway pressure), where appropriate, reducing their symptom burden and possibly improving any associated complications and quality of life.

Associated health problems

A wealth of research shows a close relationship between OSA and a number of adverse cardiovascular conditions. For instance, epidemiological data suggests that between 30 and 50 per cent of hypertensive patients have OSA and the condition is present in up to 90 per cent of those with resistant hypertension. Having OSA is a risk factor for ischaemic stroke, ischaemic heart disease, atrial fibrillation and type 2 diabetes.

Likewise, having OSA impacts on mental health and wellbeing, and is known to be a risk factor for road traffic accidents, especially where patients experience daytime sleepiness. Some evidence also points to an increased risk of death among those with untreated OSA.

Treatment

The use of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) has become the gold standard treatment for OSA. CPAP is essentially a non-invasive breathing support machine that makes use of mild pressure delivered via a nasal or facial mask. This pressure is designed to keep the airways open during sleep, preventing narrowing or collapse.

CPAP is now the first-line therapy for patients with moderate to severe OSA. There is evidence that the treatment leads to improvements in daytime sleepiness, fatigue and quality of life. CPAP is also effective at lowering blood pressure, which is important given how many people with hypertension have OSA.

An alternative is the use of an intra-oral mandibular advancement device (MAD), which can be fitted by a dentist. The device holds the lower jaw and tongue forward, allowing more space to breath and to prevent snoring. It is most suited to those who snore and have mild OSA but no daytime sleepiness.

In the recently published CRESCENT trial, the comparative effectiveness of CPAP and MAD at reducing blood pressure was examined. Over a six-month period, the results showed that the two interventions were non-inferior (i.e. not different).Another option is surgery such as tonsillectomy – if there is evidence of nasopharyngeal obstruction.

Lifestyle modification

It might seem appropriate to advise patients with OSA to lose weight. However, according to a 2021 Cochrane review, there are no randomised trials assessing the effectiveness of these interventions.

Despite this, a trial published in July found that weight loss did in fact reduce OSA, as well as improving patients’ levels of sleepiness and cardiometabolic health. “Results suggest weight loss should be the primary focus of treatment for patients with OSA and obesity,” say the authors.

Case study: Successful pharmacy-based screening service

Analysis of patients attending a community pharmacy-based private screening service for sleep disorders suggests that it is both feasible and acceptable to patients, according to a report by Newcastle University’s Dr Adam Rathbone.

The service screened and assessed patients who presented at the pharmacy with a sleep-related problem, providing advice on the most appropriate course of action. Patients were recruited via a number of routes. These included self-referral for those with insomnia or snoring; after seeing information on the service within the pharmacy; or by their GP or directly by the pharmacist while receiving other pharmacy services such as blood pressure checks or weight management advice.

Individuals were assessed using a screening tool (SnorerPharmacy) and the pharmacist discussed possible treatment options with the patient. This ranged from lifestyle advice (e.g. weight loss), further investigations such as home sleep apnoea testing supplied by the pharmacy, referral to a sleep-trained dentist or to a secondary care sleep clinic.

Of the 50 patients who accessed the service, 62 per cent met the threshold for home sleep apnoea testing and were referred to a sleep clinic, while 22 per cent were referred to a sleep-trained dentist, sleep practitioner (4 per cent) or given lifestyle advice (12 per cent). Following referral to secondary care, 39 per cent were diagnosed with obstructive sleep apnoea and 3 per cent with central sleep apnoea.

Dr Rathbone’s report describes one patient, who serves to highlight that sleep apnoea can affect anyone. The case involved a 27-year-old female snorer who never felt fully refreshed after sleeping. She experienced extreme tiredness and fatigue, affecting her concentration and mood, and was falling asleep during the day. Following home sleep apnoea testing and a referral, severe obstructive sleep apnoea was diagnosed and she received CPAP, which significantly improved her quality of life.

Useful resources

- British Society of Pharmacy Sleep Services: bspss.org

- British Snoring and Sleep Apnoea Association: britishsnoring.co.uk

- British Sleep Society: sleepsociety.org.uk