Pharmacy First Toolkit: Shingles

In Clinical

Let’s get clinical. Follow the links below to find out more about the latest clinical insight in community pharmacy.Bookmark

Record learning outcomes

How to use this toolkit

This toolkit is designed to support pharmacists and their teams deliver the Pharmacy First and similar services in the UK for shingles. It covers:

- Assessment and decision-making about shingles

- Management of the condition

- Red flags and vaccination

After completing it you will be able to recognise the typical progression of shingles in a patient and be able to determine between those eligible for pharmacy supply of antiviral medication and when referral is necessary.

Download the Toolkit PDF here.

Introduction

Shingles (herpes zoster) is a viral infection that affects sensory nerves and the skin surface served by those nerves (dermatomes).

It can be a challenge to diagnose as the pain can precede the rash by several days. Once the rash has appeared, it does usually have a vesicular appearance and often patients will attend the pharmacy already suspecting they have shingles.

Treatment timetables are important when dealing with shingles. The sooner that antivirals are prescribed for eligible patients, the less likely it is that they will suffer post-herpetic neuralgia. This means treating all those over the age of 50 years with antivirals.

The risk of developing shingles increases as a person gets older and it predominantly affects those over 70 years of age, although it is sometimes seen in young people and children. Shingles is a reactivation of a previous chickenpox (varicella zoster) infection, sometimes from decades ago.

Post-herpetic neuralgia (PHN) occurs in up to a third of people with shingles, causing severe and debilitating pain, which can be long-lasting. It is defined as pain persisting for more than 90 days after rash onset and is more common, and tends to be more severe, in older people.

The overall annual incidence in the UK is estimated to be 1.85-3.9 cases per 1,000 population, increasing with age from less than two cases per 1,000 in people younger than 50 years to 11 cases per 1,000 in people aged 80 years or older. The lifetime risk of developing shingles is 20-30 per cent and the risk increases with age.

The provision of antiviral medication (aciclovir and valaciclovir) from community pharmacies has the potential to improve access to treatment within the crucial three-day period after the shingles rash appears. This early intervention can help reduce the severity and duration of shingles.

There is also good evidence that shingles vaccine can prevent the disease in older people.

Key facts

- Shingles is a reactivation of a previous chickenpox infection and is more likely to occur in older people.

- The most common complication of shingles is post- herpetic neuralgia (PHN).

- Actively encouraging eligible patients to have the shingles vaccine is a key public health intervention.

- Early diagnosis and prompt treatment with antivirals (aciclovir and valaciclovir) can reduce the severity and duration of shingles.

- To be most effective oral antivirals should be started within 72 hours of the shingles rash appearing.

Risk factors for shingles

- Increasing age: Shingles can occur at any age, but the incidence increases as a person gets older

- Being immunocompromised including:

o HIV infection

o Lymphoproliferative malignancies

o Immuno suppressive treatment, including long-term corticosteroids

o Organ transplantation, including bone marrow transplants - Psychological factors including depression, and physical, emotional and sexual abuse. Other contributing factors may include financial stress, inability to work and an inadequate social support environment

- Certain comorbidities including:

o Diabetes

o Rheumatoidarthritis

o Asthma and COPD

o Chronic kidney disease

o Systemic lupus erythematosus

o Wegener’s granulomatosis

o Malignancies

Chickenpox and shingles

Primary infection with varicella zoster virus, usually during childhood, causes chickenpox. Although chickenpox typically presents with easily identified signs and symptoms, some cases are mild and may not be recognised.

Chickenpox in adults can be more severe. If seen within 24 hours of the rash starting an antiviral may be given, so adult patients with early chickenpox should be referred to a prescriber.

After the initial infection, the virus can settle in the body and remain dormant within the sensory nerve roots of the spinal cord or cranial nerves. Reactivation, years and sometimes decades later, is what causes shingles, with a lifetime risk of between 20-30 per cent.

It is thought that something ‘triggers’ the virus to reactivate – usually an intercurrent illness, particularly in those who are immunocompromised or on corticosteroids, but often it may not be identified. Stress and significant stressful lifetime events are often implicated.

There are several myths about the relationship between chickenpox and shingles. Community pharmacy teams have a role to play in explaining that:

- People do not “catch” shingles – it only appears in those who have previously been infected with chickenpox

- Those who have not had chickenpox cannot get shingles because there is no dormant infection to be reactivated

- Most adults will have had chickenpox – many will have had it during childhood and do not remember or were not aware of the diagnosis

- Shingles can be infectious and cause chickenpox in people who have not had it. Healthy people who have already had chickenpox will not be at risk

Patients with suspected shingles should be advised to:

- Avoid contact with people who have not had chickenpox, particularly pregnant women, the immunocompromised (e.g. those on chemotherapy or corticosteroids) and babies younger than one month of age

- Avoid sharing clothes and towels

- Wash their hands often

Is it shingles?

Many patients describe a prodromal phase with abnormal skin sensations and pain in the affected dermatome (an area of skin served by an individual nerve root).

The pain can be described as burning, stabbing or throbbing, can be intermittent or constant, and may be so severe that it interferes with sleep and quality of life. Headache, photophobia, malaise and fever (less common) may also occur as part of the prodromal phase.

If patients are seen at this point, it can be difficult to be sure of the cause in the absence of a rash. A good policy is to ask the patient to return straight away if a rash occurs. Some GPs will start oral antiviral therapy if they believe shingles is imminent (although this use is controversial).

Within two to three days (sometimes longer), a rash typically appears in a dermatomal distribution. The rash starts as maculopapular (red, raised) lesions, then develops into clusters of vesicles (small blisters), with new vesicles continuing to form over three to five days, before resolving over seven to 10 days. The vesicles burst and this releases varicella zoster virus.

The rash is usually itchy and tingly and can be very painful. Unlike most other rashes, it is unilateral – either on the left or right side of the body – and does not usually cross the mid-line of the body, but there may occasionally be a slight spread to the other side around the skin over the spine.

Healing of the affected skin occurs over two to four weeks and the damage from infection can cause scarring and permanent pigmentation.

Most cases of shingles involve the thorax, trunk and abdomen. A problem with diagnosis is the extent to which the rash can vary. This is why PGDs for community pharmacy supply of aciclovir and valaciclovir are very specific about the scope of the infection and which patients can be treated.

The rash may be atypical in certain groups – for example, older people (in whom the rash may not be vesicular) and in immunocompromised patients, when the rash may be severe or long- lasting. Symptoms can also be more widespread for immunocompromised people and affect multiple dermatomes.

Although pain is a common feature, some people, particularly younger patients, suffer little discomfort. If there is doubt over the diagnosis, these cases should be referred to a GP, alongside those in whom there are red flags.

Red flags

The vast majority of cases of shingles are unlikely to be associated with severe complications. However, those involving the eyes, nose or ears that relate to cranial nerve involvement, those affecting multiple dermatomes and those with suspected bacterial superinfection need urgent same-day referral.

Immunocompromised patients, including those on systemic corticosteroids or chemo- therapy, should also be referred urgently. The key red flags are:

- Any involvement of the forehead, nose or eye (or with visual symptoms). Known as herpes zoster ophthalmicus infection, this affects the ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve, which also innervates the eyeball.

- Hutchinson’s sign (a rash on the tip, side or root of the nose) indicates an increased likelihood of eye inflammation and permanent corneal nerve damage or denervation. However, rarely it presents as an unexplained red eye without an obvious rash. Complications include keratitis, optic neuritis, retinitis, glaucoma and blindness, and it requires urgent specialist treatment.

- Involvement of the ear. Herpes zoster oticus (Ramsay Hunt syndrome) occurs when the virus affects the facial nerve. The first sign is often deep, severe ear pain. It is characterised by lesions in the ear, facial paralysis (Bell’s palsy), and associated hearing and vestibular symptoms.

- Shingles in pregnancy. This may need antiviral treatment under specialist care.

- A person who has suspected shingles where the rash is severe, widespread or they are systemically unwell (which may signify more widespread dissemination of the virus).

- Immunocompromised people and children who have suspected shingles.

- Involvement of more than one dermatome.

- Superinfection of skin lesions. Secondary infection of the lesions, usually with staphylococcal or streptococcal bacteria, may occur and rarely can result in cellulitis, osteomyelitis or life-threatening complications.

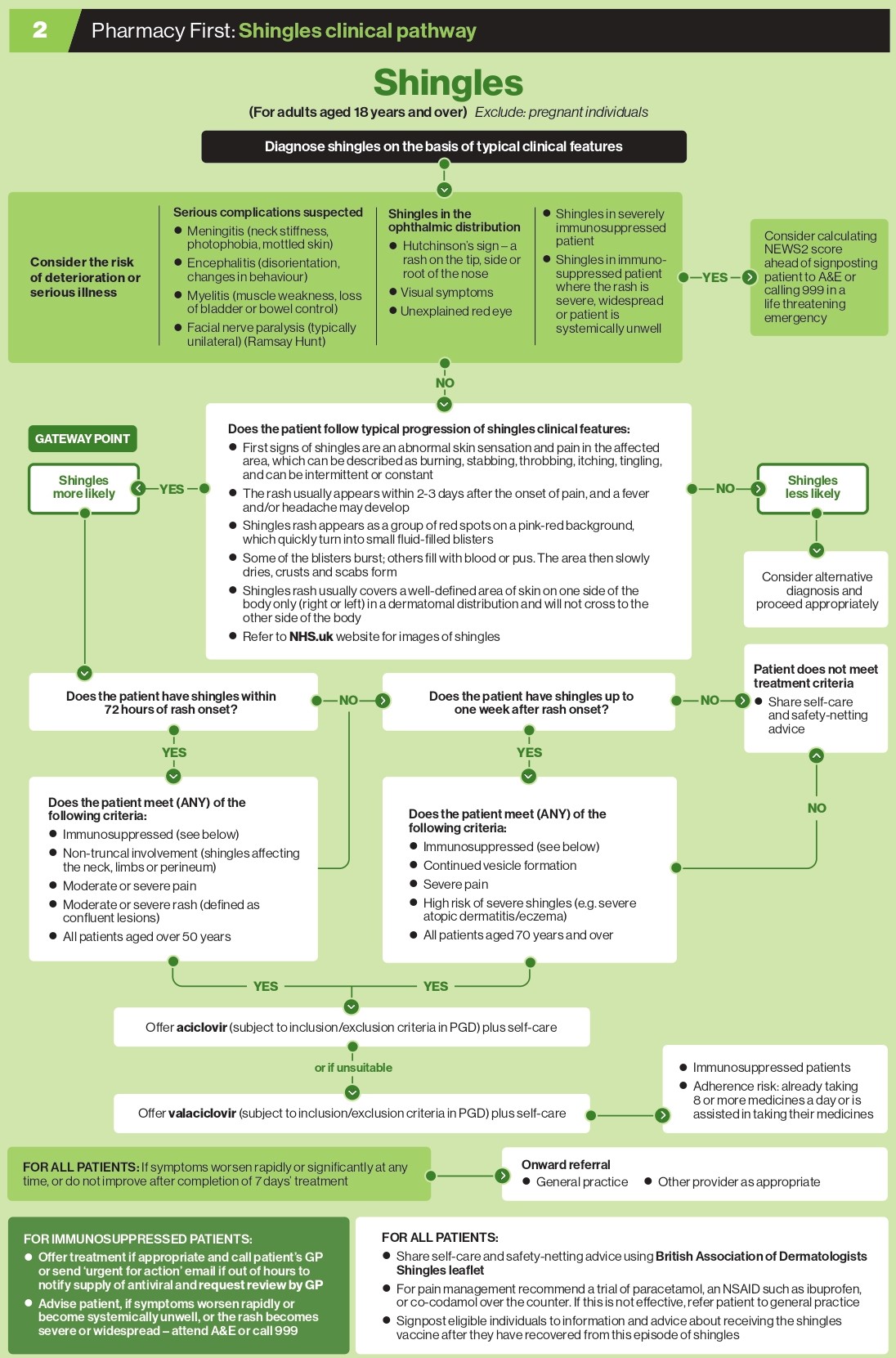

Clinical progression to the Gateway Point

- First signs of shingles are abnormal skin sensation and pain in the affected area, which can be described as burning, stabbing, throbbing, itching, tingling and can be intermittent or constant.

- The rash usually appears within 2-3 days after the onset of pain, and fever and/or headache may develop.

- Shingles rash appears as a group of red spots on a pink-red background, which quickly turn into small fluid-filled blisters.

- Some of the blisters burst; others fill with blood or pus. The area then slowly dries, crusts and scabs form.

- Shingles rash usually covers a well-defined area of skin on one side of the body only (right or left) and will not cross to the other side of the body, in a dermatomal (area of skin served by an individual nerve root) distribution.

If patients show this clinical progression, then shingles is likely and the Gateway Point has been reached.

Treatment options and practical advice

Practical advice for managing shingles is to wear loose-fitting clothes to reduce irritation, and to cover lesions that are not under clothes with a non-sticky dressing while the rash is still weeping. Patients should be advised to avoid work, school or day care if the rash is weeping and cannot be covered. Since people could catch chickenpox from someone with shingles if they have not had it before, patients should try to avoid:

- Anyone who is pregnant and has not had chickenpox before

- People with a weakened immune system

- Babies less than 1 month old

If the lesions have dried or the rash is covered, avoidance is not necessary.

Topical creams and adhesive dressings should generally be avoided as they can cause irritation and delay rash healing.

Other advice includes:

- Keep the sores clean and dry, but do not use scented soaps or bath oils and do not rub too hard as this will delay healing

- Do not let dressings or plasters stick to the rash

- Use a cold compress several times a day (ice cubes or frozen vegetables wrapped in a tea towel or a gel ice pack) may also help

Pain

The pain from shingles can range from mild to severe. Adults with mild pain can try paracetamol alone or in combination with codeine or ibuprofen. If this does not work or the person presents with, or develops, severe pain, referral is indicated.

Prescribers may offer a trial of treatment intended for neuropathic pain, usually amitriptyline (off-label use), duloxetine (off-label use), gabapentin or pregabalin.

Antivirals

For early cases of shingles, a course of oral aciclovir or valaciclovir may be used. There is evidence that the earlier treatment is started within 72 hours of rash onset, the more it may reduce the severity and duration of a shingles episode.

Pharmacists are now able to initiate this early treatment. Community pharmacy PGDs, for example in Scotland, make more specific requirements for treatment initiation, usually relating to restricting it to within 72 hours of onset, to those with a single affected dermatome on the torso and in patients aged over 18 years.

In England, both the aciclovir and valaciclovir PGDs list patient inclusion criteria as a diagnosis of shingles within 72 hours of rash onset AND ANY of the following:

- Non-truncal involvement (e.g. shingles affecting the neck, limbs or perineum)

- Moderate or severe pain

- Moderate or severe rash (defined as confluent lesions)

- Aged over 50 years

OR

Diagnosed with shingles within seven days of rash onset AND ANY of the following:

- Continued vesicle formation

- Severe pain

- High risk of severe shingles (e.g. severe atopic dermatitis/eczema)

- Aged 70 years and over

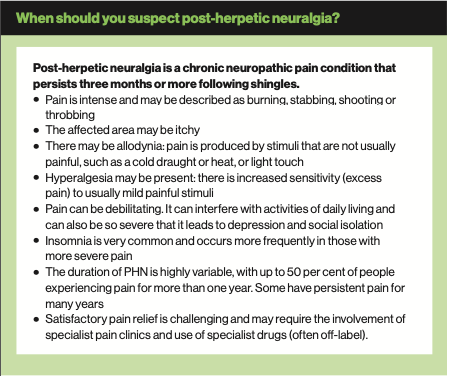

Post-herpetic neuralgia

Following the rash, persistent pain at the site – post- herpetic neuralgia (PHN) – can develop. It is seen more frequently in older people and results from peripheral nerve damage caused by the herpes zoster virus. Pain that persists for 90 days or more after the onset of the rash is a commonly accepted definition for PHN.

On average, PHN lasts from three to six months, but can persist for longer, sometimes years. The severity of pain can vary and may be constant, intermittent or triggered by stimulation of the affected area, such as wind on the face (allodynia).

The incidence of PHN is strongly related to age, ranging from 7 per cent in people aged between 50- 59 years to 21 per cent of those aged 60-69 years; 29 per cent aged between 70-79 years; and 34 per cent in those over the age of 80 years.

Vaccination

The most effective way of preventing PHN is with a herpes zoster (shingles) vaccine. Two vaccines are currently used in the NHS:

- Zostavax – a live attenuated vaccine given once

- Shingrix – a recombinant vaccine given twice

No booster dose is administered subsequently. Studies have shown that giving older people (adults aged over 60 years) the vaccine boosts waning immunity and significantly reduces morbidity from both shingles and PHN. If shingles does develop, symptom severity is greatly reduced and the incidence of PHN drops by two-thirds.

Herpes zoster vaccines are usually well tolerated and recipients experience few systemic side-effects. Protection lasts for at least 10 years.

The NHS shingles vaccination programme began in 2013, using Zostavax, initially for patients aged over 70 years. As it is a live attenuated vaccine it is contraindicated in immunosuppressed people, pregnant women and children. In 2021 Shingrix was introduced for severely immunocompromised patients.

In the first five years of the routine programme using Zostavax in England (2013-18) there were significant reductions in hospitalisation for both shingles and PHN, and in consultations for PHN. These reductions were consistent with effectiveness in the routine cohorts (vaccinated aged 70+ years).

Overall, in England, an estimated 40,500 GP consultations and 1,840 hospitalisations were averted through vaccination with Zostavax.

Since September 2023 the provision of shingles vaccine by the NHS was changed - both in the product used and age threshold. There is evidence that Shingrix has greater efficacy and provides a substantially longer duration of protection from shingles than Zostavax, although the drawback is that for a full response it has to be given in two doses at least eight weeks apart.

As it is a non-live recombinant vaccine it can be given to immunocompromised patients.

The Shingrix vaccine has replaced Zostavax in the routine shingles programme and so a two-dose schedule is now required for all patient cohorts. It can be safely given at the same time as the flu jab.

- For immunocompromised patients: The eligible cohort of patients has expanded to all patients aged 50 years and over (with no upper age limit). The programme aims to catch all severely immunocompromised individuals aged 50 years and over within the first year (see Green Book shingles chapter 28a for eligibility criteria). The second dose should be given eight weeks to six months after the first dose for this cohort.

- For immunocompetent patients: The eligible cohort of patients will expand to all those aged over 60 years, implemented in two stages over 10 years.

For these people, the second dose can be given six to 12 months after the first dose.

During stage 1 of the revised programme (September 2023 to August 2028), Shingrix will be offered to those turning 65 and 70 years on or after September 1, 2023.

Zostavax will be offered to persons aged between 70 to 79 years that were eligible for the vaccination programme before September 1, 2023. Once all stocks of Zostavax are exhausted, these individuals can be offered Shingrix if they have not previously been given a shingles vaccine.

During stage 2 (September 2028 to August 2033): Shingrix will be offered to those turning 60 and 65 years of age. From September 1, 2033, and thereafter, Shingrix will be offered routinely at age 60 years.

A longer version of this Toolkit can be found at Pharmacy Magazine under Pharmacy First.

Test your knowledge

Case study

Lisa, aged 57 years, comes to see you on Monday morning as over the weekend she developed a rash on her back. You get consent to examine Lisa and there is a maculopapular rash on the lower left-hand side extending towards the middle of her back.

1. Which of the features below are consistent with a diagnosis of shingles?

a) There is prodromal phase with abnormal skin sensations and pain in the affected dermatome

b) The rash crosses the mid-line

c) The rash appears within 2-3 days of the prodromal phase

d) The maculopapular rash develops into clusters of vesicles

Lisa tells you that she experienced some odd sensations in the same area prior to the development of the rash and that the rash is now painful. She also has a sore head and feels more tired than normal. Lisa is immunocompromised, but the rash is not widespread and she is not systemically unwell.

2. Is it appropriate to offer antiviral treatment to Lisa?

a) Yes, aciclovir for 7 days

b) Yes, valaciclovir for 7 days

c) No, she should be referred to A&E

d) No, she should be referred to her GP practice

3. As Lisa is aged over 50 years old and is immunocompromised, you offer a course of valaciclovir for 7 days. What else should you do?

a) Call her GP to advise of the supply and request a review

b) Advise her that shingles usually resolves within 4 weeks

c) Advise Lisa to attend A&E if symptoms worsen rapidly, she becomes systemically unwell, or the rash becomes severe or widespread

d) Advise her to stay off work for 7 days to avoid transmission of chickenpox to work colleagues

MCQs

4. What is the first-line treatment for shingles under the PGD?

a) Oral aciclovir

b) Oral valaciclovir

c) Topical aciclovir

d) Topical aciclovir plus oral aciclovir

5. In which circumstances is it appropriate to offer antiviral treatment if the rash onset was more than 72 hours but less than 1 week ago?

a) It is never appropriate

b) It is always appropriate

c) In people aged 70 years or over

d) For people in severe pain

6. Which of the following are inclusion criteria for the PGD?

a) People aged over 12 years People aged over 18 years

b) People who are severely immunosuppressed

c) People aged over 50 years within 72 hours of rash onset

7. What dose of aciclovir should be provided?

a) 800mg five times a day for 7 days

b) 800mg five times a day 5 days

c) 1,000mg three times a day for 7 days

d) 1,000mg three times a day for 5 days

8. Which of the following are exclusion criteria for the PGDs?

a) Aged under 18 years Pregnancy

b) People with non-truncal involvement

c) People who are immuno- suppressed with mild rash

Case study and questions provided by Agilio, author of NICE Clinical Knowledge Summaries (CKS), which has developed free Pharmacy First e-learning courses. Register at https://learn.clarity.co.uk/Courses/pharmacy-first

Answers

1. a, c, d 2. b 3. a, b, d 4. a 5. c, d 6. b, d 7. a 8. a, b

Useful resources

NHS Pharmacy First service specification, clinical pathways and PGDs

NICE CKS Shingles (including details about severe complications)

NHS Health A-Z Shingles

NHS Health A-Z Shingles vaccine

Note: For a comprehensive compendium of useful service and clinical resources, see online version of this Pharmacy First toolkit at Pharmacy Magazine

Back to top