In Clinical

Follow this topic

Bookmark

Record learning outcomes

All body organ systems demonstrate reduced functionality with ageing. But as the only visible organ, ageing of the skin in particular has a major impact on how people perceive themselves and the impression they make on others.

Skin appearance greatly affects psychological wellbeing and for some people age-related changes can be deeply distressing, reducing quality of life.

Excluding skin cancers and pressure ulcers, this article will discuss the physiological changes associated with skin ageing and some related problems, and examine ways of maintaining skin health in older adults.

Structure and functions

Although just a few millimetres thick, the skin is the heaviest organ in the human body, weighing anywhere between 3.5 and 10kg and typically covering an area equivalent to between 1.5 and 2m2. The skin is composed of two layers – the epidermis (which itself has several layers) and an underlying dermis.

The main cellular component of the epidermis are keratinocytes, a type of cell that is continually renewed approximately every 28 days. Keratinocytes are produced in the basal (base) layer of the epidermis and undergo a series of changes as they migrate through the different layers to ultimately form the stratum corneum. This uppermost layer provides the skin’s barrier function and consists of 15 to 20 sheets of flattened keratinocytes embedded within what amounts to a lipid cement.

Within the stratum corneum, keratinocytes contain natural moisturising factor (NMF), a mixture of low molecular weight compounds, including urea and glycerol, that possess water retaining properties. NMF is needed to maintain adequate levels of hydration in the epidermis and to stop the skin from drying out.

In addition to providing a barrier function, the epidermis contains several other specialised cells. These include, for instance, antigen-presenting Langerhans cells, which form part of the innate immune system and play a pivotal immune surveillance role. Along the basal layer of the epidermis are melanocyte cells, which produce the pigment melanin – important for protecting cellular DNA against the damaging effects of UV radiation. The skin also contains pre-formed vitamin D, which is converted into an active form following exposure to UVB radiation. Finally, epidermal Merkel cells provide sensitivity to mechanical stimuli.

The epidermis has two key appendages that invaginate the dermis: sweat glands, which help with temperature regulation, and pilosebaceous follicles. These follicles are the source of body and scalp hair and have an associated sebaceous gland that secretes sebum, a waxy material that helps with skin lubrication.

The underlying dermis contains nerve fibres and blood vessels. Since the epidermis is avascular, nutrients are supplied from the dermis and this is achieved via rete pegs, a series of finger-like epidermal protrusions into the dermis.

The dermis itself serves to provide structural support and flexibility to the skin and contains two key proteins: collagens and elastin, which are synthesised by fibroblast cells housed within the dermis. In addition, fibroblasts produce a gel-like material known as the extracellular matrix.

This contains glycosaminoglycans, a sugar-protein complex that, together with collagens and elastin, gives strength and elasticity to the skin.

Key facts

- Skin ageing is associated with a number of structural and functional changes that are bothersome to many people

- While it is impossible to prevent ageing, there are steps that can be taken to replenish stratum corneum lipids, prevent xerosis and maintain the skin’s protective barrier function

- Initiating conversations with older patients about their skin care can help pharmacy teams detect problems and make suggestions with a view to optimising their skin health.

The ageing process

There are two forms of skin ageing: intrinsic and extrinsic. Intrinsic ageing represents the normal chronological process. It is unavoidable and genetically determined and leads to a number of functional changes, which are outlined in the box on the next page. In contrast, extrinsic ageing occurs as a result of cumulative exposure to environmental factors such as smoking, pollutants and UV radiation.

The impact of UV radiation on the skin is referred to as photo-ageing and involves the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which cause irreparable and cumulative damage to cellular DNA. ROS also increases the activity of collagenase enzymes, degrading both collagen and glycosaminoglycans, impairing the structural integrity of the skin and leading to the formation of wrinkles.

The skin contains various antioxidant systems that are capable of repairing damage induced by ROS. However, with advancing age, the body’s ability to deal with ROS declines, causing further damage. Although the number of melanocyte cells reduces with age, this reduction is uneven, particularly in sun-exposed areas of the skin. The net effect is the appearance of irregular pigmentation (solar lentigo or age spots).

Age-related problems

A recent systematic review that included 97 studies of community dwelling older adults

(over 60 years of age) identified the most common skin problems as:

- Androgenetic alopecia (up to 83 per cent prevalence)

- Seborrhoeic keratosis (up to 78.8 per cent)

- Solar lentigo (up to 71.6 per cent)

- Actinic keratosis (up to 69.4 per cent)

- Fungal infections (up to 64 per cent)

- Xerosis (up to 60 per cent).

Androgenetic alopecia

The underlying cause of androgenetic alopecia (male/female pattern baldness) is an age-related interruption of the normal hair growth cycle. This cycle involves three phases: anagen, the growth phase; catogen, during which growth stops; and telogen, the resting stage, when new hairs start to form before beginning to grow.

In androgenetic alopecia, there is miniaturisation of the pilosebaceous follicle, driven by elevated amounts of the androgen dihydrotestosterone. This miniaturisation not only shortens the anagen phase but also converts normal scalp hair into

thinner and lighter vellus hair. In other words, hair not only becomes thinner and lighter but also fails to grow sufficiently to penetrate through the follicular opening, leading to baldness.

Unfortunately, there are limited treatment options for androgenetic alopecia in older adults. Although minoxidil is licensed for hair regrowth, its use is restricted to those under 65 years of age. Finasteride 1mg is an option for men. It works by inhibiting the enzyme 5-alpha reductase, which converts testosterone into dihydrotestosterone,

thus limiting follicular miniaturisation.

However, most of the efficacy data for finasteride comes from studies in those aged 18 to 48 years, and the drug is not available on the NHS. There is some evidence to suggest that finasteride may be effective in older adults, but as it is most effective before the onset of follicular miniaturisation, it is less likely to work in older men who have already experienced this process.

Seborrhoeic keratosis

Seborrhoeic keratosis, also known as basal cell papilloma, are harmless skin growths that have a ‘stuck-on’ appearance. The cause is unclear but might be related to genetics or even excessive sun exposure.

A recent Australian study observed how nearly a quarter of 15 to 30-year-olds had a seborrhoeic keratosis, which potentially supports a causative role for sunlight. Although benign, seborrhoeic keratosis lesions can enlarge, catch in clothing and subsequently bleed and result in a secondary infection. Consequently, patients often request that they are removed either by cryotherapy or cut off with curettage.

Solar lentigo (age or liver spots)

Solar lentigo (plural lentigines) is related to excessive exposure to sunlight. Since these lesions are benign, no treatment is required.

Actinic keratosis

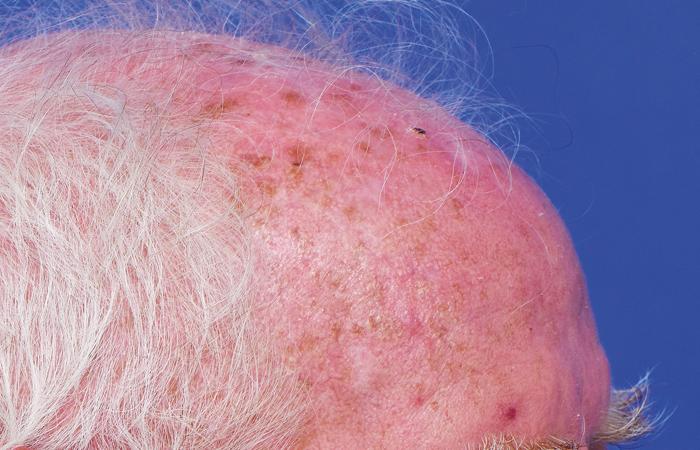

Actinic keratoses are markers of chronic sun damage and therefore normally appear on areas of the body such as the face, scalp and the dorsum of the hands. In the earliest stages, lesions are best felt rather than seen and the skin is often described as feeling like sandpaper.

These are premalignant skin lesions with the potential to undergo malignant transformation into a squamous cell carcinoma. However, the rate of conversion for an individual lesion is less than 1 per cent a year, although this risk increases when there are more lesions present.

Individual lesions can be treated with liquid nitrogen cryotherapy, but in practice, many older adults experience

actinic damage over a large area of skin, such as the scalp (known as ‘field changes’). With a higher number of lesions and within this actinic field, it is impossible to predict which ones might undergo malignant transformation.

Consequently, it is recommended that these actinic fields are treated. Appropriate therapies include 5-fluorouracil, imiquimod or diclofenac gel. In most cases, field-directed therapy reduces the number of lesions. It is also important to recognise that some lesions undergo spontaneous remission. Once they have resolved, the use of sun protection measures (e.g. broad spectrum sunscreens, avoiding the sun between 11am and 3pm) will help to minimise the risk of developing new lesions.

Fungal infections

Opportunistic fungal infections reside within the epidermis. In younger adults, shedding of epidermal cells prevents such organisms from becoming established. In contrast, older adults are more susceptible to infections because of a reduction in the number of Langerhans cells and a decrease in the replacement of keratinocytes.

While such infections can be managed with systemic antifungals, the use of these drugs in older adults can be problematic. For example, all systemic azole antifungals are hepatotoxic, so liver function tests are needed before commencing treatment.

There is also an increased risk of drug inter-actions, especially since older adults tend to be on polypharmacy regimens. Alternatively, topical azoles or allylamines (e.g. terbinafine) can be used.

Xerosis (dry skin)

The combination of lower production of intercellular lipids, NMF and sebum excretion decreases the water content of the stratum corneum, leading to dry skin.

Once the skin becomes dry, it can crack and these cracks provide an entry portal for micro-organisms and cutaneous infection. Numerous studies have shown that the skin’s pH increases from being slightly acidic towards neutral in older adults, which in turn also impairs the skin’s barrier function.

As older adults feel the cold more than younger people do, several common practices tend to exacerbate xerosis. For example, the use of fan heaters and other sources of low humidity heat like central heating causes further drying of the skin. In addition, taking a hot bath or shower and using soaps and detergents will strip the skin of its natural lipids. This is particularly troublesome for older adults, whose skin naturally produces fewer lipids, again worsening dryness. Using soap-free cleansers with a pH of four to five and taking warm rather than hot baths and showers helps to minimise this effect.

Asteatotic eczema

This is the most common form of eczema in older adults. It presents with dry and inflamed areas of skin, often on the shins. The condition tends to be worse during the winter months and is largely due to skin dryness, although diuretics, hypothyroidism and malignancies are also potential causes.

Asteatotic eczema can be managed with the use of emollients, together with mild to moderate potency topical steroids where inflammation is a prominent feature. Patients should also be advised to wash with emollient products and avoid soaps. Emollients containing humectants such as glycerol and urea attract and hold water in the stratum corneum, replicating the effect of NMF.

Intrinsic ageing: key skin changes

In the epidermis

- The normal life cycle of a keratinocyte is around 28 days but this slows down by 30 to 50 per cent by age 80 years

- The epidermis thins, largely because of a flattening of its rete pegs and decreased production of keratinocytes

- Keratinocytes produce less natural moisturising factor, and sebaceous gland activity and epidermal production of lipids reduce, leading to increased water loss and drier skin

- Sweat gland output is lower in older adults, so the risk of hypothermia is greater

- The number of Langerhans cells falls, altering the immune response, increasing the risk of skin infections

- The density of pilosebaceous follicles reduces.

In the dermis

- The thickness of the dermis decreases with advancing age

- Fibroblast activity lessens, reducing production of collagen and glycosaminoglycans, ultimately decreasing skin strength and elasticity

- Loss of collagen gives rise to wrinkling and sagging skin

- Blood flow to the skin reduces by as much as 40 per cent

- Blood vessels lose elasticity, which can reduce blood flow to the extremities

- The vasoconstrictor response to cold is impaired, leading to excessive heat loss and, ultimately, hypothermia.