In Clinical

Follow this topic

Bookmark

Record learning outcomes

Learning objectives

After reading this feature you should be able to:

- Understand the widespread and growing prevalence of allergies in the UK

- Help patients and caregivers understand the nature of allergy

- Recognise the psychological impact of allergies on sufferers.

Allergy UK estimates that 44 per cent of British adults live with at least one allergy.

Between 10 and 15 per cent of children and 26 per cent of UK adults have allergic rhinitis (AR), says the charity. Prevalence is thought to have risen by a third in the past 20 years. Meanwhile, up to 10 per cent of adults and children live with food allergies, and one in 11 children and one in 12 adults are treated for asthma.

Given that allergies and hypersensitivity disorders are so common, it is perhaps surprising that care is often imperfect. NICE has noted, for example, that “emollients [for eczema] are typically under-prescribed and under-used. This results in suboptimal treatment”.

A recent Lancet paper commented that highly effective therapies have helped to drive a marked improvement in asthma (including allergic asthma) morbidity and mortality in the past 15 years. Nevertheless, the review added that “undertreatment is still common”.1 So, given the huge number of patients with allergies, how can pharmacy teams improve outcomes?

A good place to start is by helping patients and caregivers understand the nature of allergy.

Essentially, allergies arise when an allergen enters the body. A complex comprising an IgE antibody bound to its high-affinity receptor on mast cells and basophils captures the allergen.

The complexes then cross-link. This activates mast cells and basophils, which release the inflammatory mediators that underlie allergic symptoms.2

Allergic reactions arise within minutes of exposure to an allergen, so they differ from other immune responses, which typically take longer. The rapid onset seems to reflect the particularly high affinity between IgE and its receptor, and mast cells’ exquisite sensitivity: very few receptors on mast cells need to bind the allergen to trigger ‘immediate hypersensitivity’ reactions.2

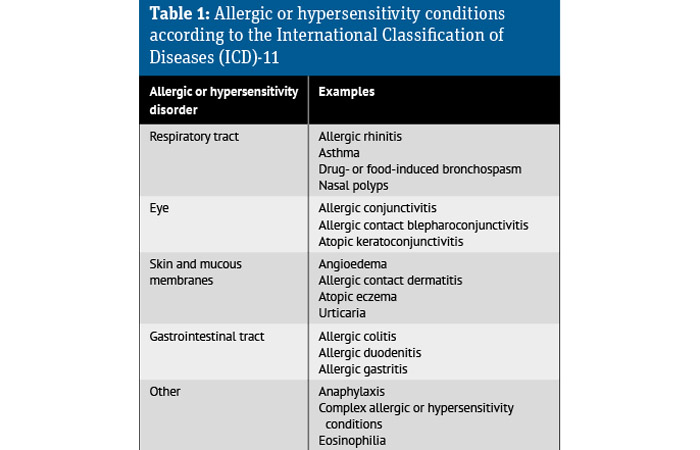

Allergies arise in any tissues populated by IgE and mast cells, such as the respiratory tract, eyes, skin and gastrointestinal tract.2 In people with allergic asthma, allergens trigger bronchospasm causing symptoms such as wheeze and breathlessness. The allergic response promotes airway inflammation, hyper-responsiveness and mucus hypersecretion. These changes contribute to asthma’s hallmark: variable airflow obstruction.1 But this isn’t the whole story.

Inflammatory mechanisms

Several inflammatory mechanisms contribute to asthma.1 For example, between 40 and 70 per cent of asthma patients show an immune pattern called type 2 inflammation, often driven by IgE and characterised by large numbers of eosinophils in the tissues.3

Type 2 inflammation evolved to counter infestations of parasitic worms. Asthma patients with eosinophilia tend to respond to inhaled corticosteroids4 but inflammation driven by neutrophils seems to underlie some cases of asthma in people with low levels of type 2 inflammation and steroids are typically less effective.4 After checking adherence and inhaler technique, patients with poorly controlled asthma should be referred.

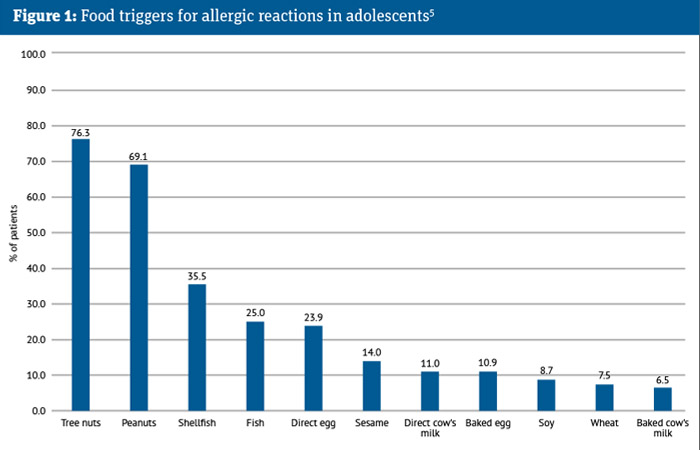

As allergies arise in any tissue populated by IgE and mast cells, many people are allergic to more than one allergen. Allergy UK estimates that 48 per cent of British adults with allergy react to more than one allergen. For instance, some 80 per cent of people with asthma have AR. A study of 94 children aged between 10 and 14 years with food allergies reported that they reacted to, on average, three food allergens, although this varied from one to 11 (see Figure 1).5 A third (36.2 per cent) of the 94 children experienced an allergic reaction and 8.5 per cent had to use their adrenaline autoinjector in the six months before the study.5

Nature and nurture

Allergies arise from the interaction between each patient’s genetic make-up and the environment. For instance, alterations in skin bacteria (microbiota) can trigger atopic dermatitis (AD) in genetically susceptible people.6 About 80 per cent of people with eczema harbour Staphylococcus aureus in their lesions (skin affected by AD).

Japanese researchers found that 45 per cent of infants at one month and 49 per cent at six months of age were colonised with S. aureus. Previous studies had suggested that S. aureus colonises the healthy skin of 5 to 10 per cent of people older than two years of age.7

Skin colonisation with S. aureus at six months of age increased the risk of developing AD at one and two years of age by about five-fold. At one and two years of age, 24.8 and 24.0 per cent respectively of children colonised with S. aureus developed AD.7

Researchers are actively investigating the role of the microbiome and the extent to which pro- and prebiotics help prevent AD and other allergies, with some encouraging results. However, further studies are needed.8

Eczematous lesions and intense itch (pruritus) are AD’s most common symptom and sign respectively.9 Eczema causes lighter skin to become itchy, inflamed and red. Darker skin affected by eczema appears itchy, brown, purple, grey or ashen. These visible changes hide marked skin damage and inflammation in the skin’s upper layer (stratum corneum) that contributes to itch.

Scratching is hard to resist but can lead to scarring and lichenification as well as releasing more proinflammatory mediators that exacerbate eczema and xerosis (dry skin).10,11 Atopic dermatitis, however, is more than skin deep: there is a two-way relationship between allergies and the mind.

Staph aureus at six months increases the risk of developing AD

Excess salt and allergic reactions

Excess salt makes hypertension more likely. But skin is also thought to store sodium and higher levels seem to worsen autoimmune conditions and chronic inflammation.16

An analysis of 215,832 UK adults, aged, on average, 56.3 years found that each gram increase in estimated 24-hour urine sodium excretion increased AD risk by 11 per cent,

AD severity by 11 per cent and active AD by 16 per cent.

In a group of 13,014 people from the US, AD risk rose by 22 per cent for each gram increase in dietary sodium.16 Salt may at least partly explain why AD increases the risk of cardiovascular disease by 10-20 per cent.16

Interestingly, a German textbook suggested a low-salt diet for AD back in 1921.16 It is clear there is still much to learn about the biological basis of allergic reactions.

Psychological link

In 1886, an American physician published the case of a woman who was allergic to roses. Even the sight of an artificial rose triggered asthmatic exacerbations.

It is also known that people with dissociative identity disorder can have one personality that experiences allergies and others that do not, while placebo responses among allergic people are among the strongest in clinical studies.12

The reality of life with a serious allergy can impose a considerable psychological toll. People with food allergies, for example, continually need to watch for and avoid possible allergens. They need to remain vigilant for allergic symptoms and rely on easy access to adrenaline autoinjectors.5

Perhaps not surprisingly, the study of 94 adolescents with food allergies reported that 37.2 per cent showed scores above the threshold for clinical anxiety. Indeed, more than a quarter experienced scores above the threshold on the separation anxiety, generalised anxiety disorder, social anxiety, panic disorder and school avoidance subscales.5

According to Allergy UK, up to 57 per cent of adults and 88 per cent of children with AR have sleep problems, leading to daytime fatigue, somnolence and poor cognitive functioning. Clinical Knowledge Summaries suggests asking about allergies’ impact on quality of life, including sleep, concentration, mood, behaviour, fatigue, leisure activities, school and work.

Taking a good history

A good clinical history helps identify the cause, possible allergens and risk factors. CKS suggests asking about the type, timing, severity, frequency and persistence of symptoms and where they emerge (e.g. indoors or outdoors), which may help identify triggers. As a rule, people with eczema should avoid or minimise exposure to irritants, such as wool, detergents, psychological stress, and, in those who are sensitised, foods, inhalants or contact allergens.9,13

Meanwhile, the number of risk factors continues to grow. For example, after adjusting for asthma, AR, respiratory allergies, parental smoking and socio-demographics, children with at least one parent who vaped were 24 per cent more likely to have AD than controls.14

And in people aged 60 years and older, and adjusting for confounders, participants who received any antihypertensive were 29 per cent more likely to develop eczema than controls, according to an analysis of UK primary care data.

Antihypertensives may be associated with 43,500 new cases of eczema annually among older adults in the UK,15 a point to consider during medication reviews. Calcium channel blockers, diuretics and angiotensin receptor blockers show a particularly strong association with eczema.15

When to refer

Pharmacists should refer patients with symptoms that could suggest an alternative diagnosis. According to CKS, for example, red flags in a patient with AR symptoms include unilateral effects, discoloured nasal discharge, recurrent nosebleeds, facial or nasal pain, or loss of sense of smell. Pharmacists should also refer children under the age of two years with continuous symptoms of rhinitis.

CKS also lists the differential diagnoses of atopic eczema, which include: psoriasis; allergic contact dermatitis (which can trigger atopic eczema); seborrhoeic dermatitis; dermato-

phytosis (fungal skin infection); scabies or other infestations; and food allergy. Refer if there is any diagnostic ambiguity.

Pharmacists should also refer when a first-line treatment, such as adequate emollient use or an OTC remedy, does not adequately improve symptoms. In some cases, a GP may refer the patient for specialist tests, such as skin prick testing (SPT) or measuring IgE levels to allergens.

In the case of AR, further investigations are usually only required if the allergen causing it can be avoided (which can be difficult so confirmation helps decide if avoidance is feasible or even possible), or there is diagnostic doubt or a poor treatment response.

NICE notes that SPT has a better positive predictive value than serum testing and provides immediate results. However, recent antihistamine, tricyclic antidepressant and topical corticosteroid use can suppress the SPT response. Up to 15 per cent of people with a positive SPT do not develop symptoms when exposed to the allergen.

Pharmacists should reinforce that a positive SPT does not confirm that a particular allergen is the cause, unless the history confirms the link. Doctors may request serum IgE testing when SPT is not possible or the results are ambiguous.

Nevertheless, IgE levels do not necessarily reflect clinical severity. Specialists may suggest other tests are required where there is diagnostic doubt or an inadequate response to treatment.

Scottish hay fever trial

Pharmacy teams have a key role in managing allergies. A recent trial enrolled seven pharmacists and seven pharmacy assistants from 12 Scottish community pharmacies to help improve patients’ ability to self-manage intermittent AR.

Trained staff in six pharmacies delivered the Help for Hay Fever service, aimed at improving self-management of triggers and symptoms, to 60 customers. Sixty-five customers at six control pharmacies received usual care.

At least one staff member from each pharmacy attended a three-hour training event. Correct answers by participants on a test about intermittent AR knowledge improved from 58 per cent before training to 85 per cent following the event. Scores on the mini-Rhinoconjunctivitis Quality of Life Questionnaire between baseline and after one and six weeks suggested “a small overall treatment effect in the intervention group”.

The improved quality of life was especially marked for practical problems and nasal symptoms. “Longer-term follow-up in a definitive trial is required to ascertain whether any differences are real and sustainable,” the researchers concluded.17

References

1. Lancet 2023; 401:858-873

2. Frontiers in Immunology 2012; 3:229

3. Lancet 2020; 395:371-383

4. British Medical Bulletin 2020; 133:16-35

5. Journal of Pediatric Psychology 2024; DOI: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsae026

6. Nature Reviews Disease Primers 2018;4: DOI:10.1038/s41572-018-0001-z

7. Science Translational Medicine 2020; 12

8. Allergy and Clinical Immunology: In Practice 2024; DOI: 10.1016/j.jaip.2024.04.048

9. Lancet 2020; 396:345-360

10. American Family Physician 2020; 101:590-598

11. British Journal of Nursing 2009; 18:872, 874, 876-7

12. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 2020; 117:10983-10988

13. Clinical and Experimental Dermatology 2013;3 8:231-8; quiz 238

14. JAMA Dermatology 2024; DOI: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2024.1283

15. Ibid. jamadermatol.2024.1230

16. Ibid. jamadermatol.2024.1544

17. npj Primary Care Respiratory Medicine 2020; 30:23